Shaping the Stein collection’s Dunhuang corpus (2): the items from Cave 17’s ‘miscellaneous’ bundles

In a previous blog post, we looked at the instrumental role played by Wang Yuanlu during the selection of the items from the Cave 17. Wang, who directly chose from the small repository what to hand over to Stein for inspection, was very keen to divert his attention from the so-called ‘regular’ bundles, which were composed for the most part of Buddhist sutras in Chinese and Tibetan. During their first ever transaction, which took place between 21 May and 6 June 1907, Wang Yuanlu therefore began by handing over the ‘miscellaneous’ bundles, which he seemed to hold in low estimation.

To Stein’s delight, these contained mixed and diverse materials, such as manuscripts in non-Chinese languages, illustrated scrolls, paintings, drawings, ex-votos, textiles, etc. Stein picked out any of the items that jumped at him as being particularly interesting and made sure to put them aside for ‘further examination’, the phrase that he used to refer to their removal in his transaction with Wang.

This blog post focuses on several of the artworks and manuscripts extracted from the ‘miscellaneous’ bundles that made their way into the Stein collection(s). Identifying items in current collections as having come from these requires a bit of detective work, based mostly on the descriptive information provided in Stein’s expedition report, Serindia, as well as the number (so-called Stein number) that he attributed to each of these items and any of the photographic evidence available.

Paintings and other “art relics”

The miscellaneous bundles were filled with pictorial works, including silk paintings with triangular tops and streamers, which Stein recognised as “once having been intended for temple banners” (Stein, 1921: 811). He usually found them tightly rolled up.

The other banner, 1919,0101,0.100 (Ch.xxvii.001), depicts three scenes from the Life of the Buddha, in a landscape setting: the Five Companions in a thunderstorm; Śākyamuni, emaciated and in meditation inside a rocky cave; and Śākyamuni emerging from the Nairanjana River with the aid of a spirit. It measures 69 cm x 19.30 cm.

The ‘miscellaneous’ bundles revealed some large silk paintings too, which Stein did not unfold at the time to avoid damaging them. In his own words, “some were found in a state of mere crumpled-up packets of smoke-begrimed silk” (Stein, 1921: 811). One such painting, reproduced in Serindia's plate LIX, depicts the Paradise of Bhaisajyaguru. It measures 152.3 cm high by 177.8 cm wide. In the centre of the composition, which is set in a landscape, the Medicine Buddha is flanked by the bodhisattvas Mañjuśrī, Samantabhadra and several attendants. Thanks to its inscriptions in Chinese and Tibetan, the painting has been dated to 836, although it was possibly produced later (Galambos, 2020: 183).

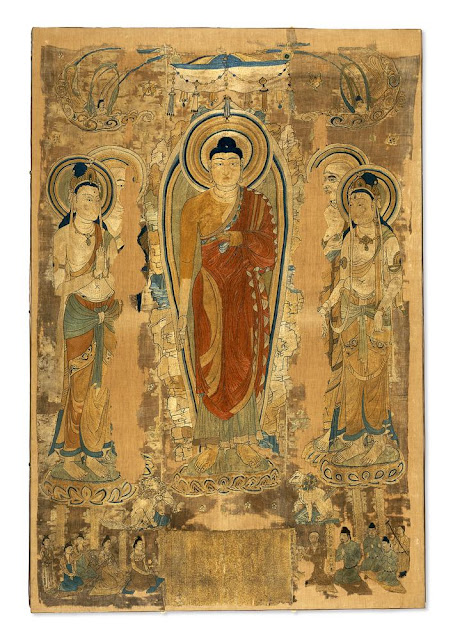

Finally, underneath the neat or ordered ‘regular’ bundles containing Buddhist sutras, were more ‘miscellaneous’ bundles that Wang used to level the ground and serve as a foundation basis for the piles of ‘regular’ bundles. They contained many more paintings and textiles, including a splendid embroidery representing Buddha with two disciples (Stein, 1921: 823–824).

Stein explained in his report that he put away the “best pictures on silk, linen, and paper I could lay my hands on” but was not faced with any opposition from Wang Yuanlu. To him, this seemed to confirm that Wang did not care too much about this type of object (Stein, 1921: 812).

Manuscripts in Chinese and Tibetan

As highlighted in Stein’s report, “The ‘miscellaneous’ bundles had proven from the first to contain hundreds of leaves from Tibetan Pothis. The packets of leaves were usually mixed up in great confusion” (Stein, 1921: 816). Nonetheless, several of the Tibetan texts that emerged from these were also written in a scroll form and made of coarse paper and appear to have been copies of the Aparimitayus Sutra, such as the manuscripts numbered ‘Ch.05’ in Plate CLXXIII.

In addition to those, there was an abundance of monastic records in Chinese:

“Mixed up with these disarranged leaves, Chinese and Tibetan rolls, and portions of large Tibetan pothis, there were convolutes of miscellaneous Chinese papers, written on detached sheets” (Stein, 1921: 811).

Several of these Chinese papers were actually monastic documents, letters and accounts that the British-Hungarian explorer learned to unpick from the Chinese Buddhist texts in which they were embedded (Stein, 1921: 819). Plate CLXVIII in Serindia shows a selection of such manuscripts, including the testament of a nun, dated to 15 November 865 and signed by several witnesses (Giles, 1935: 1029).

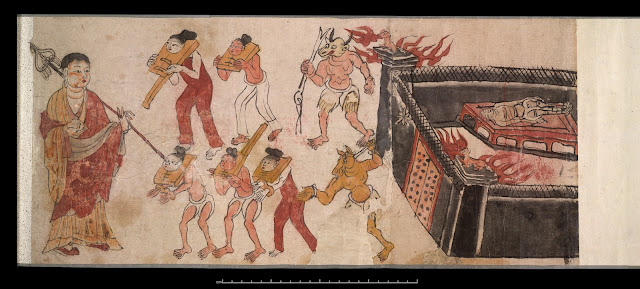

The copy of the Sutra of the Ten Kings, which is now in the British Museum, is one of the illustrated scrolls that was removed from these bundles by Stein and taken to Great Britain (Stein, 1921: 822). In this fragmentary apocryphal sutra, five kings of the underworld are represented, each seated behind a table, attended by the recorders of a person's good and evil deeds and by individuals driving the souls before the court.

Many woodblock prints, whose artistic value and interest could be recognized by Stein even “without any expert knowledge” were also hidden in the ‘miscellaneous’ bundles. One of the most significant pieces is no other than the printed copy of the Diamond Sutra dated to 868, which he presented as “an excellently preserved roll, with a well-designed block-printed frontispiece” (Stein, 1921: 822). This manuscript, Or.8210/P.2 (Ch.ciii.014), is the earliest known, complete printed book with a date on it. As indicated by the colophon, it was commissioned by a certain Wang Jie, who had it made for universal distribution on behalf of his two parents.

Manuscripts in Sanskrit, Khotanese and Uyghur

Although manuscripts in Chinese and Tibetan languages were predominantly represented among the items deposited in Cave 17, the ‘miscellaneous’ bundles revealed a wealth of documents in Sanskrit and other Central Asian languages and scripts, reflecting Dunhuang’s connections to the wider world. These finds, which were also in a variety of formats, contributed to Stein’s portrayal of Cave 17 as a “polyglot library” (1921: 813).

For instance, it was from the mixed bundles that he recovered an incomplete manuscript in Sanskrit inscribed on palm leaves, IOL San 1492 (Ch.0079.a). This is a copy of the Perfection of Wisdom Sutra in 100,000 Sections of which only 69 folios have survived. It is believed to have been originally written in northern India before being transported to Dunhuang. The mixed bundles also contained pothis, such as the Jivapustaka dated to the tenth century. This bilingual medical text in Sanskrit and Khotanese languages consists of 71 folios and belongs to the Ayurvedic tradition. Currently at the British Library, it is catalogued under the shelfmarks IOL Khot 87/1 to IOL Khot 110/2 (Ch.ii.003).

Stein extracted several scrolls bearing texts in Brahmi script (Stein, 1921: 814). One such example is IOL Khot S 46 (Ch.c.001), a spectacular vertical scroll with a painted silk cover decorated with confronted geese. It is almost 22-metre long and was found in an excellent state of conservation, leading Stein to describe it as “outwardly the most striking among the non-Chinese manuscript finds” (Stein, 1921: 815). The scroll was copied in the mid-10th century for a Buddhist patron, who requested long life for himself and his family in return. It contains six different texts: the first two are incantations (dhāraṇī) in Sanskrit; the following four are a mixture of sutras and confession texts (deśanā) in Khotanese.

Finally, there were also remains of Uyghur manuscripts in the ‘miscellaneous’ bundles: “apart for the texts written on the reverse of Chinese rolls, they comprised documents on loose leaves and a few texts written in the form of booklets” (Stein, 1921: 818). In his expedition report, Stein recalled that on 25 May 1907, “there emerged on the third day of my search a remarkable manuscript, exhibiting a third variety of the Syriac script transplanted to Central Asia […]” (Stein, 1921: 819). It contained the beautifully written and almost complete text of the Xuastwanift, a confessional prayer book of Manichaean Uyghurs.

Conclusion

While Wang Yuanlu may not genuinely have considered the ‘miscellaneous’ bundles to be “rubbish” as stated by Stein (1912: 178–9), he did not appear to be too conflicted about parting with them and certainly appeared to find them less important than the Buddhist manuscripts contained in the ‘regular’ bundles. The irony is that these very ‘miscellaneous’ bundles contained paintings and manuscripts, which Stein recognized as particularly significant and which have gained the most attention from scholars and the general public. Several of these have led to new scholarship in a wide range of fields such as Buddhism, Silk Road studies, linguistics, manuscript studies and history of art to name a few. They highlight the diversity of Cave 17’s contents and the meeting of cultures that happened in the region around Dunhuang and the Mogao Caves, which were strategically located at the crossroads between the Northern and Southern Silk Roads.

Further reading:

Galambos, I. Dunhuang Manuscript Culture: End of the First millennium, Boston; Leiden: Brill, 2020.

Giles, L. “Dated Chinese Manuscripts in the Stein Colophon”, Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, Volume 7, No. 4 (1935), 809-836.

Stein, M. A. Ruins of Desert Cathay: Personal narrative of Explorations in Central Asia and Westernmost China, London: Macmillan, 1912.

Stein, M. A. Serindia: detailed report of explorations in Central Asia and westernmost China, etc., Volumes 2 and 4, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1921.

Terzi, P. and Whitfield, S. “Reconstructing a Medieval Library? The Contents of the Manuscript Bundles in the Dunhuang Library Cave”, in Silk Roads Archaeology and Heritage, 2023 (forthcoming).

Whitfield, R. The art of Central Asia: the Stein collection in the British Museum, 3 volumes, Tokyo: Kodansha International in co-operation with the Trustees of the British Museum, 1982.

Historical photographs of materials from Cave 17 in the British Library’s collections:

- Photo 392/27(493) to Photo 392/27(496)

- Photo 392/27(509) to Photo 392/27(510)

- Photo 392/27(580) to Photo 392/27(602) and Photo 392/27(604)

Acknowledgments

The research underpinning this post was funded by the Coleridge Fellowship.

Comments

Post a Comment