Digital and physical preservation underpin much of the work carried out by the International Dunhuang Project at the British Library and are a priority for everyone involved. My position as Preservation Assistant requires me to consider long- and short-term preservation needs for the items in our care. This can involve packing items securely for transit around the library as well as longer term requirements such as appropriate storage solutions and ingesting material to the IDP website. I work alongside photographers, digitisation officers responsible for image quality control, conservators and curators to facilitate our goals of making material freely available online. It is rewarding to follow the process from start to finish and watch as more and more material becomes accessible.

Image of Paul Pelliot in the Library Cave (AP8186) and IDP Preservation Assistant Vicky Mansfield in the British Library stronghold room.

A perk of my role is discovering the wide range of decorative scrolls in the collection. Many contain vast, comprehensive illustrations. One such manuscript is the Sutra of the Ten Kings of Hell. This detailed and colourful sutra depicts the journey of a soul after death and features figures from Buddhist and Chinese beliefs.

Or.8210/S.3961 (Sutra of the Ten Kings)

Other manuscripts feature what appear to be quick sketches, often drawn on the verso. I am always fascinated by the simpler drawings that feature on the backs and in the margins of manuscripts. They are a pleasant surprise when I am checking individual items in the collection.

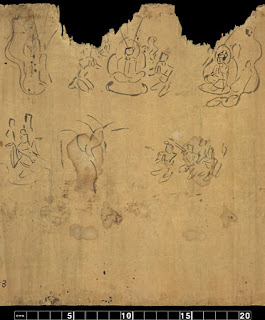

At first glance, Or.8210/S.1113 looks like any other item in the collection: when viewed from the front, it contains a fragmentary Daoist text, but the back features an extensive set of sketches. The basic forms of figures stretch across the whole manuscript and the corner of a structure or building can be seen to the left. Several of the figures appear to be buddhas sitting cross legged surrounded by kneeling people. Facial features have only been given to three of the figures. I find it interesting that those with added details are the figures in more dominant positions within the groups.

Or.8210/S.1113

When I first unrolled Or.8210/S.6030 I noticed a small line of footprints making their way towards the top of the scroll. Despite the deterioration to this part of the scroll, it is still possible to make out seven footprints. These are titled ‘Seven Paces’ which is likely to be a reference to the seven-step Daoist ritual step featured within the text, in addition to other rites.

Or.8210/S.6030

My favourite out of all the illustrations I have come across to date is the collection featured on Or.8210/S.387. The margins are filled with stylised red and black designs, but the majority of the illustrations can be found when the manuscript is turned over to show a wealth of drawings and additional text.

Detail of Or.8210/S.387

A rabbit or similar small animal can be seen in red ink with a larger version above. Three circular symbols are sitting within a flame on a lotus. These are likely to be the Three Jewels, symbolising the Buddha, the Dharma (the law) and the Sangha (the Buddhist or monastic community).

Detail of Or.8210/S.387

To the right of this in between two portraits is the cintamani, a flaming jewel said to grant all wishes. I think the most striking doodles are the four portraits that have been drawn at the other end of the manuscript. The two smaller portraits are thought to show monks. The larger and more intricate faces depict another monk and a bodhisattva.

Detail of Or.8210/S.387

Although a full translation is not available, the text is believed to be a description of a country. Could the variety of text and drawings reflect the scribbles of a person travelling, making notes and struggling with the inevitable periods of boredom? I like to think that the smaller portraits are people the writer encountered along the way. Of course, these assumptions could be incorrect but by raising these possibilities and questions, I hope illustrations such as these encourage further research into the material.

To see more examples of illustrated scrolls and further information on their contents, please follow our Twitter page for regular photographs of the collection.

By Vicky Mansfield, IDP Preservation Assistant

Love this. Great blog post Vicky!

ReplyDelete